Sigmar Polke: Higher Beings Command – at Museum Morsbroich

7. December 2023The higher beings command you to stand in a basin filled with water while wearing shoes and being surrounded by floating cucumbers. To lie under a swinging pendulum with a bellows for camera lenses between your lips and let the bellows, sensually charged, encircle the pendulum. To scratch your whole body manically. To connect with the surrounding space with long, white stripes all over your body and to pose as something between da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and Spider-Man. What conclusion can you draw from these and many other commands? Why, the whole body feels light and wants to fly.

This is the title of a 16mm film from 1969 – a joint work by Sigmar Polke and Christof Kohlhöfer – which is also the central work in this exhibition. There is something special about this film being shown again here after more than 50 years, given that the two artists created it for an exhibition in this very place, the Museum Morsbroich. Konrad Fischer had invited them to make something for an exhibition on conceptual art, Konzeption/Conception, in 1969. According to Kohlhöfer, the audience fell silent after the premiere of the film on the evening of the opening. Not surprising, since Der ganze Körper fühlt sich leicht an und möchte fliegen (The whole body feels light and wants to fly) is more or less the opposite of conceptual art and invites the viewer to immerse themselves in the world of absurd, improvised and humorous ideas, rather than dealing with strictly conceived “serious” art.

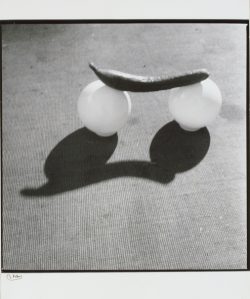

The film is just one of several collaborations between Kohlhöfer and Polke. In their joint edition …Höhere Wesen befehlen (Higher Beings Command, 1968), which lends its title to the exhibition, the beings command all sorts of ways to depict a palm tree. Here, it means depicting the highly symbolic motif of the palm tree with folding rulers, gloves, bread, buttons and so on. Polke himself becomes a palm tree. A Polke-whip or Polke as a kind of Spider-Man in stripes are motifs that show up again in the later 16mm film.

Playfulness and irony pervade Polke’s work, always showing common ideas of art and artists’ ideas about creation. In many of the drawings that make up a large part of the exhibited works, the viewer is immediately drawn into this game in which everyday things are commented on, bodies are overstretched or begin to dance, cryptic messages are given and clichés transferred, all peppered with wordplay and wit. Polke does not exclude himself from his sometimes biting sense of humour when he writes himself into artworks or history: he sticks a photo of himself onto a drawing, supposedly by Picasso, and depicts himself as the constellation “S.POLKE” in the year of the moon landing. Someone here has a sense of grandeur.

The small and very fine exhibition, which largely consists of works on paper and photographs by Polke from a private collection, spans very different series. Manipulated photocopies not only provide an insight into Polke’s eternal joy in experimentation and his use of a machine instead of a pen, but also his questioning or even reinvention of authorship in general.

Sigmar Polke, Untitled (Quetta, Pakistan), 1974, gelatin silver print on Agfa paper, overpainted with gold varnish

Manipulated black and white photographs also open doors to other worlds. They are based on photographs that Polke took while travelling in Pakistan and Afghanistan. He later reworked them using double exposures, various types of treatment with chemicals, scratching and other methods to give them a mysterious, slightly otherworldly atmosphere.

Just how crucial manipulation is to Polke’s work is demonstrated again in the modified photographs for Athanor, his exhibition in the German Pavilion at the 1986 Venice Biennale. He treated the walls of the pavilion with special substances so that they reacted to light, temperature and humidity and were therefore in a constant state of flux. The transformation lives on in his photos of that exhibition, which were then also further processed in the darkroom.

As you walk through all these many transformations in the exhibition, it becomes increasingly clear that the whole body must actually feel light and, above all, wants to fly.